The Mystery of the Rio de Janeiro Antwren (Myrmotherula fluminensis)

- Caio Brito

- Dec 15, 2025

- 8 min read

It all started with an innocent message.

On October 19, I received a note from good friend Jonathan Newman.

“I wanted to pick your brain about the Rio de Janeiro Antwren and what your opinions are. It’s obviously an enigmatic taxon but there is so little online about its validity even. I read a mist-netting study from REGUA where they caught consistent specimens but they were all luctuosa (Silvery-flanked Antwren) once they were in the hand. What is your opinion and that of the Brazilian top rank birders? Is it a thing? Is it extinct? Is it a plumage morph of luctuosa? I know what I think but maybe I’m biased haha.”

I didn’t realize it at the moment, but that message would send me down a small rabbit hole that mixed science, stories, and a pretty strange sense of loss.

It would lead me into conversations with people like Luciano Lima and Gustavo Bravo, and into one of the Atlantic Forest’s most intriguing mysteries: the case of Myrmotherula fluminensis, the Rio de Janeiro Antwren.

(Unfortunately, I was unable to reach Luiz Pedreira Gonzaga, the person who described the species)

A bird that never really existed — or maybe still does

The Rio de Janeiro Antwren was described in 1988 by Luiz Gonzaga, based on a single male specimen mist-netted in Magé, a lowland area at the base of Serra dos Órgãos, just 30 kilometers from downtown Rio de Janeiro.

That’s already remarkable. Imagine: one of the most urbanized regions in Brazil, one of the most studied birding zones in South America — and right there, a bird nobody had ever seen before.

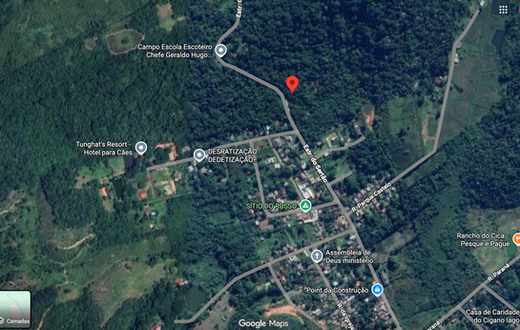

1 – First map: overview of the region with the observation point.

2 – Zoom into the area where we can observe the urbanization.

3 – The forest remnant where the Rio de Janeiro Antwren was seen.

4 – Just a few meters from the observation point, the urbanized area.

And then, nobody saw it again…

The type specimen — that one individual in the drawers of the Goeldi Museum in Belém — is all we have. It was never photographed alive, never recorded singing, never seen in a mixed flock.

It’s that one specimen stuffed under glass. That's it.

Over the years, many started to doubt whether fluminensis was a real species at all. Some argued it might just be a strange plumage variant of the [Silvery] White-flanked Antwren (Myrmotherula axillaris luctuosa), which is common in the area. Others went further, suggesting it could be a hybrid — maybe between axillaris luctuosa and urosticta, or between axillaris and unicolor.

1 – White-flanked Antwren - Photo by José Rondon

2 – Band-tailed Antwren- Photo by Gustavo Soares de Oliveira

3 – Unicolored Antwren- Photo by Leonardo Casadei

In 2017, BirdLife International even removed it from the global checklist, listing it as “not recognized.” Just like that — a species born and gone in a few lines of taxonomy.

Luciano Lima strongly disagrees with this decision and supports this as a valid species.

But as it often happens in ornithology, the story didn’t end there.

A hint from DNA

When I spoke with Gustavo Bravo, one of the leading voices in suboscine phylogenetics, he told me something that made me sit up straight.

“When we sequenced all the Myrmotherulas for the 2020 phylogeny, we included that one specimen from the Goeldi Museum — the only known fluminensis. And what we found is that it doesn’t fall with axillaris at all. It actually clusters closer to Myrmotherula iheringi, a clade of Amazonian antwrens.”

That’s pretty cool. The bird named after Rio de Janeiro might not even belong to the Atlantic Forest lineage.

Bravo added, “We’re still testing hypotheses — including whether it could be a hybrid between urosticta and axillaris. But the data published so far suggest it could be a valid species, something distinct. The story isn’t over.”

He mentioned that he and his team are working on a follow-up paper, about 35% done, which could clarify these relationships once and for all.

What’s striking is that this bird — whether hybrid or valid — represents a forgotten piece of evolutionary history. A small gray-and-black antwren that may carry the genetic information of lineages long separated by rivers, mountains, and the “dry-forest corridor”.

The search: back to where it all began

In 2018, Luciano Lima and Rafael Bessa led a project supported by American Bird Conservancy, titled “Searching for the Rio de Janeiro Antwren: a forgotten Atlantic Forest bird.”

Their goal was simple in theory, daunting in practice: go back to where the type specimen was collected, and look for the bird.

They began at the Campo Escoteiro de Magé, the exact spot where Gonzaga’s mist net once stood, and then expanded their search to nearby fragments below 300 meters in elevation — lowland forests now mostly surrounded by cattle pastures and expanding urban zones.

Using playback of related species — Myrmotherula iheringi, Formicivora iheringi, and even Glaucidium brasilianum (to stir up mobbing) — they spent mornings exploring every possible patch of habitat that could still shelter fluminensis.

They recorded 206 species, including 40 Atlantic Forest endemics, among them uncommon birds like White-necked Hawk, Golden-tailed Parrotlet, and Unicolored Antwren. They even rediscovered a long-absent species from the area — the Rio de Janeiro Antbird (Cercomacra brasiliana) — which hadn’t been seen locally since the 1950s.

1 – Ihering's Antwren - Photo by Gilberto Nascimento

2 – Narrow-billed Antwren - Photo by Guto Balieiro

3 – Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl - Photo by Jeanne Martins

But not a single sign of the Rio de Janeiro Antwren.

Luciano and Rafael in the field during the “Searching for the Rio de Janeiro Antwren: a Forgotten Atlantic Forest Bird” expedition in 2018.

A landscape of loss and resilience

Reading Luciano’s report feels like stepping into a place at once full of life and on the brink of erasure.

The Baixada Fluminense region — once lush with lowland Atlantic Forest — is now a patchwork of forest islands adrift in a sea of urbanization. Satellite images from 1984 and now show how the green recedes year by year, replaced by gray sprawl and red dirt.

During the expedition, the team found hunter traps, palm trees cut for palm heart extraction, new roads being bulldozed into the forest. Even the entrance of one promising site had a sign reading “Trail closed — do not insist.”

Still, in the midst of it all, birds endure…

Luciano and Rafael’s conclusion was clear and cautiously hopeful:

“Between the species’ type locality and REGUA there are still many forest areas to search. More extensive and continued fieldwork is necessary before we can reach a conclusion about the current status of the Rio de Janeiro Antwren.”

Talking to the people who know the land

Luciano and Rafael also spent time speaking with local residents and hunters, showing drawings of the bird and asking if anyone had seen something like it.

Most people had never heard of it. A couple of hunters claimed recognition, describing a small antwren that “eats insects in the understory,” but when shown a photo of the much more common Silvery-flanked Antwren, they hesitated — maybe that was what they’d seen after all.

What if it’s still there?

I asked Luciano what he really thinks.

He paused and said, “Look, we didn’t find it. But that doesn’t mean it’s gone. The lowlands are messy. Access is hard, and much of it is unsafe because of the local security situation. There are still pockets of good forest — we just need people who can go, listen, and look again.”

He mentioned how inspiring it was to see how many birders reached out after his Avistar 2018 presentation, realizing for the first time that such a bird might still exist.

That’s the power of stories: they can reignite a search.

Luciano Lima during Avistar 2018, presenting: Rio de Janeiro Antwren: The History of a Mystery

Between doubt and faith

In the world of birding, there’s a fine line between skepticism and hope. We know that some species vanish quietly — gone long before anyone notices. Yet, sometimes, they reappear in the most unexpected ways.

Think of the Kinglet Calyptura, another “lost bird” of the Atlantic Forest. Thought extinct for decades, it was rediscovered in 1996 not far from Rio, after 119 years unseen.

Same for the Blue-eyed Ground-Dove, rediscovered by Rafael Bessa almost 80 years after the last record.

If that can happen, why not this one?

Somewhere in those tangled forests below Serra dos Órgãos, there could still be a pair of small gray antwrens flitting through the vines, silent to playback, unknown to eBird, unseen by human eyes for nearly 40 years.

And that thought alone — that tiny, stubborn possibility — is enough to keep the mystery alive.

What this bird represents

To me, the Rio de Janeiro Antwren is more than an unresolved taxonomic case. It’s a mirror of the Atlantic Forest itself — an ecosystem fragmented, overlooked, but still holding a few secrets.

It’s also a reminder of how science, conservation, and passion intersect. A single museum specimen, a few grams of tissue, can still inspire conversations across continents and decades.

I think about Gustavo Bravo’s words — how finishing that next paper could help “get some funding for the local people around Rio to go and look for it.” That’s the kind of hope we need: not abstract optimism, but action rooted in curiosity.

As soon as that paper comes out, and proves the Rio de Janeiro Antwren is a valid species (is it, really?) I'll be the first to stir up a searching expedition.

Because in the end, rediscovering a bird isn’t just about ticking a species off a list, it’s about restoring a connection — like the vivid example of the Blue-eyed Ground-Dove.

The spirit of curiosity

Maybe we’ll never see Myrmotherula fluminensis again. Or maybe one day, someone walking a trail near Magé will hear a faint chip note that doesn’t match anything they know, and that’s how it’ll begin again — just like Jonathan’s message began this story.

That’s the beauty of birding. It keeps us humble.

Every once in a while, a simple question — “Is it a thing? Is it extinct? Is it just a morph?” — reminds us how little we truly know, and how much there’s still to learn.

So, here’s to the Rio de Janeiro Antwren — whether real, hybrid, or lost...

Thank you

Big thanks to Jonathan for raising this question and to Gustavo and Luciano for the helpful conversations and feedback.

Bibliography:

Lima, L. M. & Bessa, R. (2018). Searching for the Rio de Janeiro Antwren: a forgotten Atlantic Forest bird. Instituto Butantan – Bird Observatory, supported by American Bird Conservancy.

Gonzaga, L. P. (1988). A new antwren from southeastern Brazil. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club, 108:132–135.

Personal communications: Jonathan Newman, Luciano Lima, Gustavo Bravo.

https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/rdjant2/cur/introduction?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?avibaseid=AD84BFB22781E89E&utm_source=chatgpt.com