How Many Amazons Are There in the Brazilian Amazon?

- Arthur Gomes, Caio Brito & Pablo Cerqueira

- 54 minutes ago

- 9 min read

When we think about the Amazon, the most common image that comes to mind is that of an immense, continuous forest, apparently uniform, stretching for thousands of kilometers. From above — whether through maps, satellite imagery, or even in the collective imagination — everything seems to belong to a single, vast ecosystem. From a bird’s perspective, however, this view is misleading.

The Amazon is not one single entity. What we broadly call “the Amazon” actually contains multiple Amazons, each with distinct bird communities shaped by rivers, habitats, geology, and evolutionary history. Understanding this complexity helps explain why species change abruptly from one side of a river to the other, why some birds occur only in very specific areas, and why no single trip can ever represent the full diversity of the Amazon.

The Amazon goes beyond terra firme forest

Before even discussing rivers as barriers, it is important to remember that the Amazon is not composed solely of terra firme forest. This is, without a doubt, the most extensive and widespread habitat, but it is far from being the only one.

Across the Brazilian Amazon, we find a wide variety of natural formations, such as seasonally flooded forests — várzea and igapó — associated with major rivers, as well as campinas and campinaranas on sandy soils, montane areas, extensive bamboo stands (taboca), and even natural grasslands known as “Campos Amazônicos” (Amazonian Fields). Each of these environments imposes different ecological challenges and, as a result, supports its own set of species, often highly specialized.

Different Amazonian habitats found across the Brazilian Amazon. From top to bottom: terra firme forest viewed from the canopy tower at Thaimaçu Lodge (left); seasonally flooded várzea forest (right); sandy-soil forest (campina) during the rainy season (left); and campina habitat during the dry season (right), exposing its white-sand soils. Each of these environments supports distinct bird communities and contributes to the Amazon’s ecological mosaic.

Photos: Caio Brito

In other words, even without considering the role of rivers as geographic barriers, there are already multiple “Amazons” defined purely by habitat diversity. From the very beginning, the Amazon forest is a mosaic.

Rivers as natural barriers: an idea that changed everything

It was in the 19th century that this perception began to take scientific shape. During his expeditions through the Amazon between 1848 and 1852, Alfred Russel Wallace observed a pattern that repeated itself with remarkable consistency: similar species, especially primates, occurred on opposite banks of large rivers but rarely crossed from one side to the other.

These major Amazonian rivers are not merely elements of the landscape; they function as biogeographic barriers that, over thousands or millions of years, have limited gene flow between populations. The result of this prolonged isolation is the replacement of sister species on opposite sides of rivers — a pattern that repeats itself across many groups of birds.

It is important to emphasize that this division is neither geometric nor symmetrical. Amazonian rivers follow the terrain, meander, change course over time, and vary enormously in width, discharge, and stability. Consequently, larger and older rivers separate communities more deeply than smaller and more recent ones.

Major interfluvia: broad but imperfect divisions

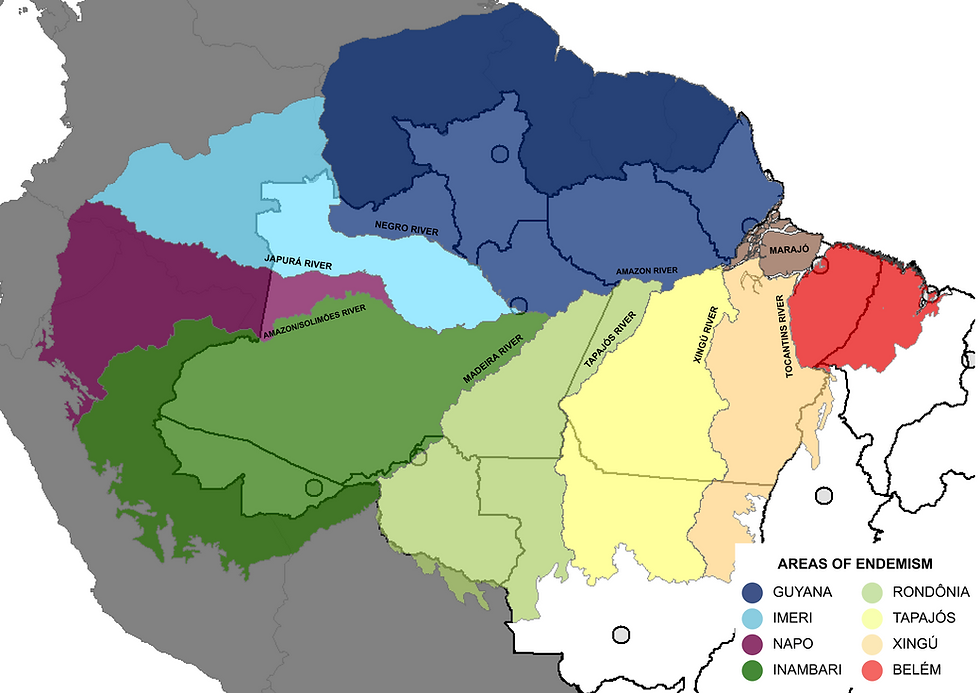

Based on these observations, it became possible to recognize large biogeographic regions within the Amazon, often delimited by the basin’s largest rivers. These major interfluvia help explain striking differences in bird community composition across the Brazilian Amazon.

In simplified terms, some of these broad regions include the Guiana Shield, the area between the Negro and Solimões rivers, the Solimões–Madeira interfluve, and the regions east of the Madeira River. Each of these areas hosts distinct assemblages of species, with numerous cases of replacement between sister species on opposite sides of major rivers.

It is important to stress, however, that these divisions do not represent regular “quadrants” on a map. They are neither symmetrical nor homogeneous. Amazonian rivers vary greatly in width, long-term stability, flow speed, and geological age. Some act as extremely effective barriers, while others allow occasional crossings or function as limits only for certain groups of birds.

These large interfluvia therefore represent a first layer of organization of Amazonian diversity. They explain broad patterns, but they are far from telling the whole story.

Amazons within Amazons: the role of smaller rivers

When we look more closely, within each major interfluve, complexity increases even further. Some smaller rivers also act as biogeographic barriers, although on a different scale. It is important to note that when we refer to “smaller rivers,” such as the Aripuanã, this scale is relative: smaller compared to the Madeira, Solimões, or Tapajós, but still larger than many rivers found elsewhere in the world.

Unlike the major Amazonian rivers, which may separate dozens of species across opposite banks, these smaller rivers often delimit the distribution of just one or a few species. Even so, the pattern is consistent and biologically meaningful.

A good example occurs in the Aripuanã River basin. In this region, certain taxa show distributions clearly associated with opposite riverbanks or specific sub-interfluvia, even in the absence of obvious changes in landscape or forest type. To field observers, these differences may seem subtle, but they are stable enough to define well-delimited areas of occurrence.

Examples of micro-endemism within a major Amazonian interfluve. Species such as Aripuana Antwren (Herpsilochmus stotzi, on the left) and Manicore Warbling-Antbird (Hypocnemis rondoni, on the right ) have distributions linked to boundaries of smaller rivers. Despite the subtle appearance of the landscape, smaller rivers can act as consistent biogeographic boundaries for some bird species. In this case, the Aripuanã River. Photos: Caio Brito

These cases demonstrate that the Amazon is not divided solely by major biogeographic boundaries. It is also shaped by a complex network of smaller limits that refine the composition of local communities. Not every river creates a new “Amazon,” but many clearly influence biodiversity at a local scale.

Endemism beyond terra firme: flooded forests and water types

Patterns of endemism in the Amazon are not restricted to terra firme forests. Flooded forests also support distinct communities and, in many cases, species with very restricted distributions.

In this context, river water type plays a fundamental role. In the Amazon, rivers are broadly classified as blackwater (igapó), whitewater (várzea), or clearwater systems, each with distinct physical and chemical characteristics. These differences directly influence riparian vegetation and, consequently, the species that depend on these environments.

Igapó (blackwater) species

Várzea (whitewater) Species

Examples of bird species associated with Amazonian flooded forests (click to see the names). Igapó forests host specialized communities distinct from those found in várzea forests. Differences in river chemistry and flooding regimes strongly influence vegetation structure and, in turn, the composition of bird assemblages across the Amazon. Photos: Pablo Cerqueira and Ciro Albano

Some birds are almost exclusively associated with specific river types or with particular stretches of a single basin. In some cases, species occur only along certain segments of large rivers, without extending throughout their entire length. These patterns remain relatively understudied but clearly show that Amazonian endemism is also strongly linked to flooded forests and river dynamics.

Tepuis: Amazonian highlands

Beyond forests and rivers, another important element in Amazonian biogeographic fragmentation is mountainous terrain. Amazonian highlands — including the tepuis — function as true ecological islands within the continuous forest, isolated by differences in elevation, climate, and vegetation.

Tepuis and other Amazonian highlands rise as isolated plateaus above the surrounding lowland forest. These ancient formations, such as the Serra do Sol in northern Brazil, create montane environments separated by elevation and climate, supporting distinct bird communities. Photos: Thiago Laranjeiras

These formations are associated with some of the region’s most classic patterns of endemism. Over time, populations isolated in these environments evolved independently, giving rise to sister species that replace one another across different mountain ranges or between uplands and the surrounding lowland forests.

Isolated highland areas within the Amazon, such as the Carajás mountain range in eastern Pará, add further complexity to the region’s biogeography. These elevated landscapes host distinct ecological conditions and are associated with bird species such as the White Bellbird (Procnias albus), which occurs in forested uplands across parts of the Amazon. Photos: Pablo Cerqueira.

In northern Amazonia, especially within the Guiana Shield, tepuis are geologically ancient and have remained relatively stable for millions of years. This helps explain why many species associated with these areas have extremely restricted distributions. In Brazil, two major groups are generally recognized: tepuis east of the Caroní River and those to the west, each with its own characteristic fauna.

These “islands of altitude” add yet another layer of complexity to the Amazonian mosaic. Even in a region dominated by continuous forest, topography creates environments isolated enough to generate new lineages and distinct communities.

What does all of this mean in practice?

When we bring together all these factors — habitat diversity, major rivers, smaller tributaries, water types, and mountainous areas — it becomes clear that the Amazon is a highly compartmentalized system. Most Amazonian bird species do not occur throughout the entire basin but are restricted to specific regions, habitats, or interfluvia.

In practical terms, this means that a single trip to the Amazon can never represent “the Amazon” as a whole. Even relatively nearby locations may host very different sets of species, especially when separated by major rivers or located in distinct interfluvia.

For birdwatchers, this explains why certain species are easily found in one region yet rare or completely absent in another, even when the landscape appears similar. Avian community composition is not random; it follows well-defined biogeographic limits, even if these are not always obvious to the naked eye.

Why are there so many Amazons?

Amazonian diversity is the result of a long evolutionary history shaped by rivers acting as barriers, contrasting vegetation and habitats, geological events, and climatic factors that promoted isolation at different temporal scales. The result is not a uniform forest, but a mosaic of Amazons, each with its own identity.

Understanding this structure changes how we view the region — and also how we explore and plan experiences in the Amazon. BBE’s itineraries are designed with this biogeographic reality in mind, deliberately crossing different interfluvia and habitats, maximizing endemism, and highlighting potential future taxonomic splits currently being studied by science.

It is precisely within this internal diversity that one of the Amazon’s greatest riches lies. The more we understand its multiple “Amazons,” the clearer it becomes that knowing the region is, above all, a process of continuous discovery.

Questions this article helps answer

Is the Amazon really one single ecosystem?

No. While often described as a single forest, the Amazon is better understood as a mosaic of distinct ecosystems. Differences in habitats, rivers, geology, and evolutionary history create multiple “Amazons,” each with its own bird communities.

Why do bird species change across Amazonian rivers?

Large Amazonian rivers act as long-term biogeographic barriers, limiting gene flow between populations. Over time, this isolation leads to the replacement of closely related (sister) species on opposite riverbanks.

How many biogeographic regions exist within the Amazon?

There is no single, fixed number. Broad regions are often defined by major rivers and interfluvia, but within these areas, additional layers of division exist. The Amazon’s biogeography is hierarchical and complex rather than neatly segmented.

Why can’t one trip represent all Amazon bird diversity?

Most Amazonian bird species are restricted to specific regions, habitats, or interfluvia. Even locations that are geographically close can host very different bird communities, especially when separated by rivers, elevation or occupying distinct habitats within the Amazon.

What is an interfluve, and why does it matter for birds?An interfluve is the land area between two rivers. In the Amazon, interfluvia often define biogeographic units where bird communities differ markedly from those in neighboring regions, playing a key role in patterns of endemism and species replacement.

Do smaller rivers also act as barriers?

Yes, although on a smaller scale. While major rivers may separate many species, smaller rivers often delimit the ranges of one or a few taxa. These boundaries are subtle but biologically meaningful and help refine local patterns of diversity.

What role do tepuis play in Amazon biodiversity?

Tepuis and other Amazonian highlands function as ecological islands. Isolated by altitude, climate, and vegetation, they host unique bird communities and some of the region’s most restricted-range species, shaped by long-term evolutionary isolation.

Why are some Amazon birds restricted to very small areas?

Highly localized distributions often result from a combination of geographic isolation, habitat specialization, river dynamics, and long-term evolutionary history. These factors can confine species to specific interfluvia, river systems, flooded forests, or mountainous areas.

Acknowledgements

We thank Thiago Laranjeiras and Luis Morais for kindly providing images and photographs that contributed to this article.

Well done, guys!